A Doll’s House

| A Doll’s House | |

|---|---|

| Written by | Henrik Ibsen |

| Characters |

|

| Date premiered | 21 December 1879 |

| Place premiered | Royal Theatre in Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Original language | Norwegian |

| Subject | The awakening of a middle-class wife and mother. |

| Genre | Naturalistic / realistic problem play Modern tragedy |

| Setting | The home of the Helmer family in an unspecified Norwegian town or city, circa 1879. |

The play is significant for the way it deals with the fate of a married woman, who at the time in Norway lacked reasonable opportunities for self-fulfillment in a male-dominated world. It aroused a great sensation at the time,[2]and caused a “storm of outraged controversy” that went beyond the theatre to the world newspapers and society.[3]

The title of the play is most commonly translated asA Doll’s House, though some scholars useA Doll House. John Simon says thatA Doll’s Houseis “the British term for what [Americans] call a ‘dollhouse'”.[6]Egil Törnqvist says of the alternative title: “Rather than being superior to the traditional rendering, it simply sounds more idiomatic to Americans.”[7]

| A Doll’s House | |

|---|---|

| Written by | Henrik Ibsen |

| Characters |

|

| Date premiered | 21 December 1879 |

| Place premiered | Royal Theatre in Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Original language | Norwegian |

| Subject | The awakening of a middle-class wife and mother. |

| Genre | Naturalistic / realistic problem play Modern tragedy |

| Setting | The home of the Helmer family in an unspecified Norwegian town or city, circa 1879. |

List of characters

-

Nora Helmer– wife of Torvald, mother of three, is living out the ideal of the 19th-century wife, but leaves her family at the end of the play.

-

Torvald Helmer– Nora’s husband, a newly promoted bank manager, professes to be enamoured of his wife but their marriage stifles her.

-

Dr Rank– a rich family friend. He is terminally ill, and it is implied that his “tuberculosis of the spine” originates from a venereal disease contracted by his father.

-

Kristine Linde– Nora’s old school friend, widowed, is seeking employment (sometimes spelledChristinein English translations). She was in a relationship with Krogstad prior to the play’s setting.

-

Nils Krogstad– an employee at Torvald’s bank, single father, he is pushed to desperation. A supposed scoundrel, he is revealed to be a long-lost lover of Kristine.

-

The Children– Nora and Torvald’s children: Ivar, Bobby and Emmy (in order of age).

-

Anne Marie– Nora’s former nanny, who gave up her own daughter to “strangers” when she became, as she says, the only mother Nora knew. She now cares for Nora’s children.[8]

-

Helen– the Helmers’ maid

-

The Porter– delivers a Christmas tree to the Helmer household at the beginning of the play.

Synopsis

Act One

The play opens at Christmas time as Nora Helmer enters her home carrying many packages. Nora’s husband Torvald is working in his study when she arrives. He playfully rebukes her for spending so much money on Christmas gifts, calling her his “little squirrel.” He teases her about how the previous year she had spent weeks making gifts and ornaments by hand because money was scarce. This year Torvald is due a promotion at the bank where he works, so Nora feels that they can let themselves go a little. The maid announces two visitors: Mrs. Kristine Linde, an old friend of Nora’s, who has come seeking employment; and Dr. Rank, a close friend of the family, who is let into the study. Kristine has had a difficult few years, ever since her husband died leaving her with no money or children. Nora says that things have not been easy for them either: Torvald became sick, and they had to travel toItalyso he could recover. Kristine explains that when her mother was ill she had to take care of her brothers, but now that they are grown she feels her life is “unspeakably empty.” Nora promises to talk to Torvald about finding her a job. Kristine gently tells Nora that she is like a child. Nora is offended, so she teases the idea that she got money from “some admirer,” so they could travel to Italy to improve Torvald’s health. She told Torvald that her father gave her the money, but in fact she managed to illegally borrow it without his knowledge because women couldn’t do anything economical like signing checks without their husband. Over the years, she has been secretly working and saving up to pay it off.

Krogstad, a lower-level employee at Torvald’s bank, arrives and goes into the study. Nora is clearly uneasy when she sees him. Dr. Rank leaves the study and mentions that he feels wretched, though like everyone he wants to go on living. In contrast to his physical illness, he says that the man in the study, Krogstad, is “morally diseased.”

After the meeting with Krogstad, Torvald comes out of the study. Nora asks him if he can give Kristine a position at the bank and Torvald is very positive, saying that this is a fortunate moment, as a position has just become available. Torvald, Kristine, and Dr. Rank leave the house, leaving Nora alone. The nanny returns with the children and Nora plays with them for a while until Krogstad creeps through the ajar door, into the living room, and surprises her. Krogstad tells Nora that Torvald intends to fire him at the bank and asks her to intercede with Torvald to allow him to keep his job. She refuses, and Krogstad threatens to blackmail her about the loan she took out for the trip to Italy; he knows that she obtained this loan by forging her father’s signature after his death. Krogstad leaves and when Torvald returns, Nora tries to convince him not to fire Krogstad. Torvald refuses to hear her pleas, explaining that Krogstad is a liar and a hypocrite and that he committed a terrible crime: he forged someone’s name. Torvald feels physically ill in the presence of a man “poisoning his own children with lies and dissimulation.”

Act Two

Kristine arrives to help Nora repair a dress for a costume function that she and Torvald plan to attend the next day. Torvald returns from the bank, and Nora pleads with him to reinstate Krogstad, claiming she is worried Krogstad will publish libelous articles about Torvald and ruin his career. Torvald dismisses her fears and explains that, although Krogstad is a good worker and seems to have turned his life around, he must be fired because he is too familial around Torvald in front of other bank personnel. Torvald then retires to his study to work.

Dr. Rank, the family friend, arrives. Nora asks him for a favor, but Rank responds by revealing that he has entered the terminal stage oftuberculosisof the spine and that he has always been secretly in love with her. Nora tries to deny the first revelation and make light of it but is more disturbed by his declaration of love. She then clumsily attempts to tell him that she is not in love with him, but that she loves him dearly as a friend.

Desperate after being fired by Torvald, Krogstad arrives at the house. Nora convinces Dr. Rank to go into Torvald’s study so he will not see Krogstad. When Krogstad confronts Nora, he declares that he no longer cares about the remaining balance of Nora’s loan, but that he will instead preserve the associated bond to blackmail Torvald into not only keeping him employed but also promoting him. Nora explains that she has done her best to persuade her husband, but he refuses to change his mind. Krogstad informs Nora that he has written a letter detailing her crime (forging her father’s signature of surety on the bond) and put it in Torvald’s mailbox, which is locked.

Nora tells Kristine of her difficult situation. She gives her Krogstad’s card with his address, and asks her to try to convince him to relent.

Torvald enters and tries to retrieve his mail, but Nora distracts him by begging him to help her with the dance she has been rehearsing for the costume party, feigning anxiety about performing. She dances so badly and acts so childishly that Torvald agrees to spend the whole evening coaching her. When the others go to dinner, Nora stays behind for a few minutes and contemplates killing herself to save her husband from the shame of the revelation of her crime and to preempt any gallant gesture on his part to save her reputation.

Act Three

Kristine tells Krogstad that she only married her husband because she had no other means to support her sick mother and young siblings and that she has returned to offer him her love again. She believes that he would not have stooped to unethical behavior if he had not been devastated by her abandonment and been in dire financial straits. Krogstad changes his mind and offers to take back his letter from Torvald. However, Kristine decides that Torvald should know the truth for the sake of his and Nora’s marriage.

After literally dragging Nora home from the party, Torvald goes to check his mail but is interrupted by Dr. Rank, who has followed them. Dr. Rank chats for a while, conveying obliquely to Nora that this is a final goodbye, as he has determined that his death is near. Dr. Rank leaves, and Torvald retrieves his letters. As he reads them, Nora steels herself to take her life. Torvald confronts her with Krogstad’s letter. Enraged, he declares that he is now completely in Krogstad’s power; he must yield to Krogstad’s demands and keep quiet about the whole affair. He berates Nora, calling her a dishonest and immoral woman and telling her that she is unfit to raise their children. He says that from now on their marriage will be only a matter of appearances.

A maid enters, delivering a letter to Nora. The letter is from Krogstad, yet Torvald demands to read the letter and takes it from Nora. Torvald exults that he is saved, as Krogstad has returned the incriminating bond, which Torvald immediately burns along with Krogstad’s letters. He takes back his harsh words to his wife and tells her that he forgives her. Nora realizes that her husband is not the strong and gallant man she thought he was, and that he truly loves himself more than he does Nora.

Torvald explains that when a man has forgiven his wife, it makes him love her all the more since it reminds him that she is totally dependent on him, like a child. He dismisses the fact that Nora had to make the agonizing choice between her conscience and his health, and ignores her years of secret efforts to free them from the ensuing obligations and the danger of loss of reputation. He preserves his peace of mind by thinking of the incident as a mere mistake that she made owing to her foolishness, one of her most endearing feminine traits.

We must come to a final settlement, Torvald. During eight whole years. . . we have never exchanged one serious word about serious things.Nora, in Ibsen’sA Doll’s House(1879)

Nora tells Torvald that she is leaving him, and in a confrontational scene expresses her sense of betrayal and disillusionment. She says he has never loved her, they have become strangers to each other. She feels betrayed by his response to the scandal involving Krogstad, and she says she must get away to understand herself. She has lost her religion. She says that she has been treated like a doll to play with for her whole life, first by her father and then by him. Concerned for the family reputation, Torvald insists that she fulfill her duty as a wife and mother, but Nora says that she has duties to herself that are just as important, and that she cannot be a good mother or wife without learning to be more than a plaything. She reveals that she had expected that he would want to sacrifice his reputation for hers and that she had planned to kill herself to prevent him from doing so. She now realizes that Torvald is not at all the kind of person she had believed him to be and that their marriage has been based on mutual fantasies and misunderstandings.

Torvald is unable to comprehend Nora’s point of view, since it contradicts all that he has been taught about the female mind throughout his life. Furthermore, he is so narcissistic that it is impossible for him to understand how he appears to her, as selfish, hypocritical, and more concerned with public reputation than with actual morality. Nora leaves her keys and wedding ring; Torvald breaks down and begins to cry, baffled by what has happened. After Nora leaves the room, Torvald suddenly senses hope, as the door downstairs is heard closing.

Alternative ending

Ibsen’s German agent felt that the original ending would not play well in German theatres. In addition, copyright laws of the time would not preserve Ibsen’s original work. Therefore, for it to be considered acceptable, and prevent the translator from altering his work, Ibsen was forced to write an alternative ending for the German premiere. In this ending, Nora is led to her children after having argued with Torvald. Seeing them, she collapses, and as the curtain is brought down, it is implied that she stays. Ibsen later called the ending a disgrace to the original play and referred to it as a “barbaric outrage”.[9]Virtually all productions today use the original ending, as do nearly all of the film versions of the play.

Composition and publication

Real-life inspiration

A Doll’s Housewas based on the life of Laura Kieler (maiden name Laura Smith Petersen), a good friend of Ibsen. Much that happened between Nora and Torvald happened to Laura and her husband, Victor. Similar to the events in the play, Laura signed an illegal loan to save her husband. She wanted the money to find a cure for her husband’s tuberculosis.[10]She wrote to Ibsen, asking for his recommendation of her work to his publisher, thinking that the sales of her book would repay her debt. At his refusal, she forged a check for the money. At this point she was found out. In real life, when Victor discovered about Laura’s secret loan, he divorced her and had her committed to an asylum. Two years later, she returned to her husband and children at his urging, and she went on to become a well-known Danish author, living to the age of 83.

Ibsen wroteA Doll’s Houseat the point when Laura Kieler had been committed to the asylum, and the fate of this friend of the family shook him deeply, perhaps also because Laura had asked him to intervene at a crucial point in the scandal, which he did not feel able or willing to do. Instead, he turned this life situation into an aesthetically shaped, successful drama. In the play, Nora leaves Torvald with head held high, though facing an uncertain future given the limitations single women faced in the society of the time.

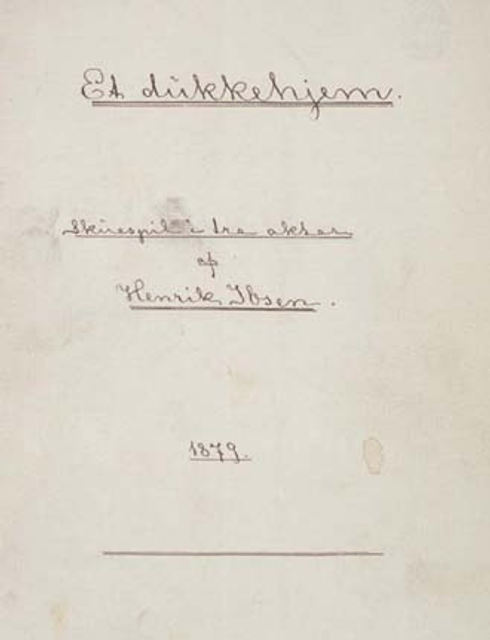

Composition

Ibsen started thinking about the play around May 1878, although he did not begin its first draft until a year later, having reflected on the themes and characters in the intervening period (he visualised its protagonist, Nora, for instance, as having approached him one day wearing “a blue woolen dress”).[13]He outlined his conception of the play as a “modern tragedy” in a note written in Rome on 19 October 1878.[14]“A woman cannot be herself in modern society,” he argues, since it is “an exclusively male society, with laws made by men and with prosecutors and judges who assess feminine conduct from a masculine standpoint!”[15]

Publication

Ibsen sent a fair copy of the completed play to his publisher on 15 September 1879.[16]It was first published in Copenhagen on 4 December 1879, in an edition of 8,000 copies that sold out within a month; a second edition of 3,000 copies followed on 4 January 1880, and a third edition of 2,500 was issued on 8 March.[17]

Production history

A Doll’s Housereceived its world premiere on 21 December 1879 at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen, with Betty Hennings as Nora, Emil Poulsen as Torvald, and Peter Jerndorff as Dr. Rank.[18]Writing for the Norwegian newspaperFolkets Avis, the critic Erik Bøgh admired Ibsen’s originality and technical mastery: “Not a single declamatory phrase, no high dramatics, no drop of blood, not even a tear.”[19]Every performance of its run was sold out.[20]Another production opened at the Royal Theatre in Stockholm, on 8 January 1880, while productions inChristiania(with Johanne Juell as Nora and Arnoldus Reimers as Torvald) and Bergen followed shortly after.[21]

In Germany, the actress Hedwig Niemann-Raabe refused to perform the play as written, declaring, “Iwould never leavemychildren!”[20]Since the playwright’s wishes were not protected by copyright, Ibsen decided to avoid the danger of being rewritten by a lesser dramatist by committing what he called a “barbaric outrage” on his play himself and giving it an alternative ending in which Nora did not leave.[22][23]A production of this version opened in Flensburg in February 1880.[24]This version was also played in Hamburg, Dresden,Hanover, andBerlin, although, in the wake of pros and a lack of success, Niemann-Raabe eventually restored the original ending.[24]Another production of the original version, some rehearsals of which Ibsen attended, opened on 3 March 1880 at the Residenz Theatre in Munich.[24]

In Great Britain, the only way in which the play was initially allowed to be given in London was in an adaptation by Henry Arthur Jones and Henry Herman calledBreaking a Butterfly.[25]This adaptation was produced at the Princess Theatre, 3 March 1884. Writing in 1896 in his bookThe Foundations of a National Drama, Jones says: “A rough translation from the German version of A Doll’s House was put into my hands, and I was told that if it could be turned into a sympathetic play, a ready opening would be found for it on the London boards. I knew nothing of Ibsen, but I knew a great deal of Robertson and H. J. Byron. From these circumstances came the adaptation calledBreaking a Butterfly.”[26]H. L. Mencken writes that it wasA Doll’s House“denaturized and dephlogisticated. … Toward the middle of the action Ibsen was thrown to the fishes, and Nora was saved from suicide, rebellion, flight and immortality by making a faithful old clerk steal her fateful promissory note from Krogstad’s desk. … The curtain fell upon a happy home.”[27]

Before 1899 there were two private productions of the play in London (in its original form as Ibsen wrote it) — one featuredGeorge Bernard Shawin the role of Krogstad.[8]The first public British production of the play in its regular form opened on 7 June 1889 at the Novelty Theatre, starring Janet Achurch as Nora and Charles Charrington as Torvald.[28][29][30]Achurch played Nora again for a 7-day run in 1897. Soon after its London premiere, Achurch brought the play to Australia in 1889.[31]

The play was first seen in America in 1883 in Louisville, Kentucky; Helena Modjeska acted Nora.[29]The play made its Broadway premiere at the Palmer’s Theatre on 21 December 1889, starring Beatrice Cameron as Nora Helmer.[32]It was first performed in France in 1894.[21]Other productions in the United States include one in 1902 starring Minnie Maddern Fiske, a 1937 adaptation with acting script by Thornton Wilder and starring Ruth Gordon, and a 1971 production starring Claire Bloom.

A new translation by Zinnie Harris at the Donmar Warehouse, starring Gillian Anderson, Toby Stephens, Anton Lesser, Tara FitzGerald and Christopher Eccleston opened in May 2009.[33]

The play was performed by 24/6: A Jewish Theater Company in March 2011, one of their early performances following their December 2010 lower Manhattan launch.[34]

In August 2013, Young Vic,[35]London, Great Britain, produced a new adaptation[36]ofA Doll’s Housedirected by Carrie Cracknell[37]based on the English language version by Simon Stephens. In September 2014, in partnership with Brisbane Festival, La Boite located in Brisbane, Australia, hosted an adaptation ofA Doll’s Housewritten by Lally Katz and directed by Stephen Mitchell Wright.[38]In June 2015, Space Arts Centre in London staged an adaptation ofA Doll’s Housefeaturing the discarded alternate ending.[39]‘Manaveli’ Toronto staged a Tamil version ofA Doll’s House(ஒரு பொம்மையின் வீடு)on 30 June 2018,Translated and Directed by Mr P Wikneswaran. The drama was very well received by the Tamil Community in Toronto and was staged again in few months later. The same stage play was filmed at the beginning of 2019 and screened in Toronto on 4 May 2019. The film was received with very good reviews and the artists were hailed for their performance. Now, arrangements are being made to screen the film,ஒரு பொம்மையின் வீடு, in London, at Safari Cinema Harrow, on 7 July 2019;[39]

Analysis and criticism

A Doll’s Housequestions the traditional roles of men and women in 19th-century marriage.[22]To many 19th-century Europeans, this was scandalous. The covenant of marriage was considered holy, and to portray it as Ibsen did was controversial.[40]However, the Irish playwrightGeorge Bernard Shawfound Ibsen’s willingness to examine society without prejudice exhilarating.[41]

The Swedish playwright August Strindberg criticised the play in his volume of essays and short storiesGetting Married(1884).[42]Strindberg questioned Nora’s walking out and leaving her children behind with a man that she herself disapproved of so much that she would not remain with him. Strindberg also considers that Nora’s involvement with an illegal financial fraud that involved Nora forging a signature, all done behind her husband’s back, and then Nora’s lying to her husband regarding Krogstad’s blackmail, are serious crimes that should raise questions at the end of the play, when Nora is moralistically judging her husband. And Strindberg points out that Nora’s complaint that she and Torvald “have never exchanged one serious word about serious things,” is contradicted by the discussions that occur in act one and two.[43]

The reasons Nora leaves her husband are complex, and various details are hinted at throughout the play. In the last scene, she tells her husband she has been “greatly wronged” by his disparaging and condescending treatment of her, and his attitude towards her in their marriage — as though she were his “doll wife” — and the children in turn have become her “dolls,” leading her to doubt her own qualifications to raise her children. She is troubled by her husband’s behavior in regard to the scandal of the loaned money. She does not love her husband, she feels they are strangers, she feels completely confused, and suggests that her issues are shared by many women. George Bernard Shaw suggests that she left to begin “a journey in search of self-respect and apprenticeship to life,” and that her revolt is “the end of a chapter of human history.”[8][44][3]

Ibsen was inspired by the belief that “a woman cannot be herself in modern society,” since it is “an exclusively male society, with laws made by men and with prosecutors and judges who assess feminine conduct from a masculine standpoint.”[15]Its ideas can also be seen as having a wider application: Michael Meyer argued that the play’s theme is not women’s rights, but rather “the need of every individual to find out the kind of person he or she really is and to strive to become that person.”[45]In a speech given to the Norwegian Association for Women’s Rights in 1898, Ibsen insisted that he “must disclaim the honor of having consciously worked for the women’s rights movement,” since he wrote “without any conscious thought of making propaganda,” his task having been “thedescription of humanity.”[46]

Because of the departure from traditional behavior and theatrical convention involved in Nora’s leaving home, her act of slamming the door as she leaves has come to represent the play itself.[47][48]InIconoclasts(1905), James Huneker noted “That slammed door reverberated across the roof of the world.”[49]

Adaptations

Film

A Doll’s Househas been adapted for the cinema on many occasions, including:

-

A 1922 lostsilent filmA Doll’s Housestarring Alla Nazimova as Nora.[50][51]

-

A 1923 German silent filmNorawas directed by Berthold Viertel. Nora was played by Olga Chekhova, who was born Olga Knipper, and was the niece and namesake ofAnton Chekhov’s wife. She was also Mikhail Chekhov’s wife.[52]

-

A 1943 Argentine film,Casa de muñecas, starring Delia Garcés, which modernizes the story and uses the alternative ending.[53]

-

Two film versions were released in 1973: one was directed by Joseph Losey, starring Jane Fonda, David Warner and Trevor Howard;[54]and the other by Patrick Garland with Claire Bloom, Anthony Hopkins, and Ralph Richardson.[55]

-

Dariush Mehrjui’s filmSara(1993) is based onA Doll’s House, with the plot transferred to Iran.Sara, played by Niki Karimi, is theNoraof Ibsen’s play.[56]

-

In 2012 the Young Vic theatre in London released a short film calledNorawith Hattie Morahan portraying what a modern-day Nora might look like.[57]

-

A scheduled 2018 film adaptation is set against the backdrop of the current economic crisis and stars Ben Kingsley as Doctor Rank and Michele Martin as Nora.[58][59]

Television

-

A live version for American TV was broadcast in 1959 which was directed by George Schaefer. This version featured Julie Harris, Christopher Plummer, Hume Cronyn, Eileen Heckart and Jason Robards.

-

In 1973 Norwegian TV produced an adaptation of A Doll’s House (Et dukkehjem)[87]directed by Arild Brinchmann and with Lise Fjeldstad[88]as Nora Helmer.

-

A 1974West Germantelevision adaptation, titledNora Helmerwas directed by Rainer Werner Fassbinder and starred Margit Carstensen in the title role.

-

In 1992, David Thacker directed a British television adaptation with Juliet Stevenson, Trevor Eve and David Calder.

Radio

-

A 6 June 1938Lux Radio Theatreproduction starred Joan Crawford as Nora and Basil Rathbone as Torvald.

-

A later version by theTheatre Guild on the Airon 19 January 1947, featured Rathbone again as Torvald with Dorothy McGuire as Nora.

-

In 2012, BBC Radio 3 broadcast an adaptation by Tanika Gupta transposing the setting to India in 1879 where ‘Nora’, now Niru, is an Indian woman married to ‘Torvald’, now Tom, an English man working for the British Colonial Administration in Calcutta; this production starred Indira Varma as Niru and Toby Stephens as Tom.[60]

Re-staging

-

In 1989, film and stage director Ingmar Bergman staged and published a shortened reworking of the play, now entitledNora, which entirely omitted the characters of the servants and the children, focusing more on the power struggle between Nora and Torvald. It was widely viewed as downplaying the feminist themes of Ibsen’s original.[61]The first staging of it in New York was reviewed by theTimesas heightening the play’s melodramatic aspects.[62]TheLos Angeles Timesstated that “Norashores upA Doll’s Housein some areas but weakens it in others.”[63]

-

Lucas Hnath wroteA Doll’s House, Part 2as a follow-up about Nora 15 years later.

-

The Citizens’ Theatre in Glasgow have performedNora: A Doll’s Houseby Stef Smith, a radical re-working of the play, with three actors playing Nora, simultaneously taking place in 1918, 1968 and 2018.[64]

-

Dottok-e-Log (Doll’s House) Adapted and Directed by Kashif Hussain was Performed in Balochi language at National Academy of Performing Arts on 30 and 31 March 2019.

Novels

-

In 2019, memoirist, journalist and professor Wendy Swallow[89]publishedSearching for Nora: After the Doll’s House.[90]Swallow’s historical novel tells the story of Nora Helmer’s life from the moment in December 1879 that Nora walks out on her husband and young children at the close of A Doll’s House. Swallow draws from her research into Ibsen’s play and iconic protagonist, the realities of the time, and the 19th-century Norwegian emigration to America, following Nora as she first struggles to survive in Kristiania (today’s Oslo) and then travels by boat, train and wagon to a new home in the western prairie of Minnesota.